Characteristic of the adventure game genre is that puzzles represent the main type of challenge presented to the player. To analyse adventure games will therefore often be a matter of investigating puzzles, for instance asking how the individual puzzles occurring in a game relate to a more general understanding of what distinguishes “puzzles” as a game genre or form. In his analysis of the textual, puzzled based genre of Interactive Fiction (IF), Nick Montfort stresses the obvious kinship between this genre and that of the literary riddle. He points to the following similarities: “Both have a systematic world, are something to be solved, present challenge and appropriate difficulty, and join the literary and the puzzling” (Montfort 2003b, 43). The comparison easily applies to another textual computer game genre as well, namely the adventure oriented MUD, the puzzle-structure of which I have discussed in previous work (most recently in Tronstad 2004).

Even if the literary is highlighted as one of the criteria uniting Interactive Fiction and the literary riddle in Montfort’s definition, I don’t think the medium of text is a precondition for the comparison to be fruitful. The other and more significant similarities identified are between factors we find on the level of genre, or form, rather than factors tied to medium. This implies that the model of the literary riddle may be transferable from text based adventure games to graphical games of the same genre.

In this paper, I will investigate this possibility by using the literary riddle as a model to analyse three puzzles of the graphical adventure game The Longest Journey (Funcom 2000). I base my analyses on the hypothesis that the model of the literary riddle may provide us with relevant, clearly defined criteria as to what distinguishes a well constructed puzzle, and thus the model may function as a useful analytical tool with which we are able to articulate what exactly it is that distinguishes a great adventure game puzzle from poor ones. In the following, before proceeding to the analyses, I will therefore present a definition of the riddle, as well as a suggestion of how our main object, the adventure game puzzle, relates to it.

Riddles and puzzles

According to Dan Pagis, in his article “Toward a Theory of the Literary

Riddle” (1996), certain conditions must be fulfilled for a text

to qualify as a riddle: It must be presented as a challenge and involve

a social situation (a riddler and a riddlee), it must have one single

correct answer, there must be a balancing between concealing and revealing

of hints, and the riddle must be soluble: “Not only in terms of

its hints but also in the nature of the subject itself. [..] The subject

must be general and familiar” (Pagis 1996, 94-95). Like the literary

figure of metaphor, the riddle establishes a world – or more precisely

– a world order, according to which it may be deciphered. This world

order necessarily has to be different from the world order we usually

subscribe to, or deciphering the riddle will not represent a challenge

to us. At the same time, the world reflected by the riddle must not deviate

too much from the world we are familiar with, as it is otherwise unlikely

that we will ever be able to recognise it. One of the challenges presented

by a riddle is thus to identify the rules according to which the proposed

world of the riddle function. The proper identification of these rules

is necessary in order to catch the solution to the riddle. This is not

to say that the riddlee identifies the rules first and then solves the

riddle: A more common experience is probably that the identification of

the rules according to which the world of the riddle functions, and the

knowledge of the riddle’s solution occur simultaneously, in one

and the same movement.

A typical adventure game puzzle fulfils many of the same requirements as the riddle: It represents a social situation in which a challenge is posed to the player, and in which there is a certain balance maintained between the hints revealed and the secrets concealed. Most often it is soluble, leading to one single correct answer (or action, rather). In the article “Toward a Theory of Interactive Fiction” Montfort defines a puzzle as “a challenge [...] that requires a non-obvious set of commands in order to be met. Non-obvious refers to a hypothetical, typical interactor encountering the work for the first time” (Montfort 2003a). To distinguish between the riddle and the puzzle, we could define the riddle as an enigmatic entity that constitutes a semantic whole – a world – in and of itself, whereas this is not a necessary condition for a puzzle. Puzzles aspire to be riddles, and may approach the form of the riddle, which constitutes their ideal form. They will qualify as puzzles even if only some of the requirements to the riddle is fulfilled, though.

Perhaps the most central feature that the riddle and the puzzle have in common is the ephemeral nature of their form and function: The moment they are solved, it is no longer possible to experience them as a riddle or a puzzle, that is, from the position of the riddlee. But even though most riddles are exhausted by being solved, according to Pagis there also exist riddles to which the transformation from veiled to unveiled adds a new and more profound level. Such riddles can be compared to poems, functioning like metaphors in which the combination of – and interaction between – two seemingly incompatible concepts create a third, new and different concept. His example is a metaphorical riddle where the solution of it is experienced as only a first step – where the real reward is the metaphorical content that the solved riddle reveals (Pagis 1996, 98). Usually when considering riddle and puzzle solving, the reward is identified as the sudden moment of epiphany in which the riddlee “sees” the solution to the problem – where she proceeds from ignorance to knowledge, from helplessness to mastery. In adventure games such epiphanies function as rewards on the way, contributing to a positive gaming experience. In order to experience the solution as an epiphany, a balance between what is concealed and what is revealed in the puzzle is required. If the puzzles are too obvious, there is little pleasure in solving them. Are they too obscure, we may be tempted to consult a walkthrough instead of using our own experience to find the correct solution, which also tends to weaken our sense of mastery and recognition in the game.

The phenomenon described by Pagis where the solution of the riddle is experienced as merely a step towards the “real reward” in the form of an aesthetic impression has its equivalent in adventure gaming as well. In its simplest form, it is the phenomenon of puzzle solving contributing to opening/revealing more of the game space to us. As solving a puzzle often contributes to spatial or conceptual discovery in the game, the subject matter of this discovery may also be experienced as a reward in itself, e.g. by appearing particularly beautiful or compelling to the player, or by contributing a significant element which adds to the experience of inhabiting an alternative reality. In Shlomith Cohen’s view, “[s]olving riddles has much to do with the ability to play with contexts, which is connected to the ability to suspend the commonly perceived reality and create alternative realities” (Cohen 1996, 302). A significant element in this context may be an element which contributes to the credibility or reality-effect of the alternative world established by the game.

In her article “Connecting through Riddles or The Riddle of Connecting” (1996), Cohen investigates the riddle from the perspective of psychoanalysis, in particular focusing on the communicative, interactive nature of riddling. Like Pagis, Cohen accentuates that the riddle always implies a social situation, regardless of the riddler being present as a fellow human being, or represented by or in a piece of text. From the perspective of the riddlee, the riddler is always perceived as a subject: the one who knows the answer. The riddling situation is thus a special case of interrogation, Cohen writes, since it implies that there already exists an answer to the question, the nature of which will appear paradoxical and non-obvious to the riddlee.

[The] riddle-work is designed to make the listener become lost in the wrong track of associations, until he finds his way back into a new, yet shared, path of associations with the riddler. In this sense, the riddler is experientially lost and found in the process of solving the riddle. (Cohen 1996, 303)

The experience of that which is unknown in the riddle manifests itself in a particular way that is also contributing to making the riddle a special case, according to Cohen. She writes:

Riddles seem to carry in them the feeling that the solution should have been known. [...] When solved, most riddles seems simple and immediately available to the listener. It becomes clear that the elements for solving the riddle was within reach, but beyond awareness. (Cohen 1996, 298)

The riddlee’s consciousness of being unaware of something which should be within reach to him, Cohen relates to Freud’s concept of the uncanny. In Freud’s theory, the uncanny is fundamentally connected to that which is familiar. It is the familiar yet strange which is scary.

Cohen’s comparing of the riddle with the uncanny, yet familiar, implies that there is an element of recognition in solving a riddle, where the information revealed is experienced as information that is already familiar. The effect of creating such an illusion of familiarity is a feature of the riddle that becomes particularly interesting in the context of adventure gaming, where both spatial and conceptual discovery are often accomplished through puzzle solving. I will return to this point later in the analyses. Now, I’d like to briefly present the game The Longest Journey, as well as the three puzzles that I have picked from it which will serve as my analytical examples.

Three puzzle examples

The Longest Journey takes place in a future world which has been

divided into the two opposite realms Stark and Arcadia. Stark is the realm

in which our adventure starts, it is ruled by science and logic whereas

the other realm, Arcadia, is ruled by magic. Our character is the young

woman April Ryan, whose mission it is to save the world by restoring its

balance. Among other tasks, this operation implies that the two divided

realms, Stark and Arcadia, must be united.

My first two examples occur in chapter two, where we are still situated in the logical realm of Stark. Stark is where April grew up, and in contrast to its magical counterpart Arcadia, it is more or less similar to our world.

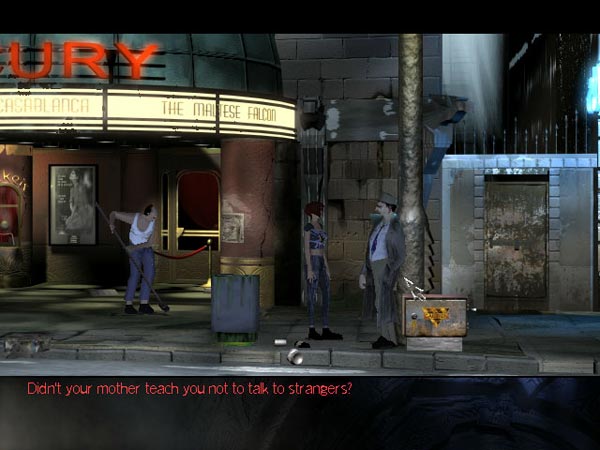

In the first example, April needs access to a fuse box, which – inconveniently – is guarded by a detective.

Copyright © Funcom 1998 - 2003

Before she can approach the box, therefore, she needs to find a way to make the detective go away. Talking to him we get to know that he just had lunch, but missed dessert, so now he has a craving for sweets. Luckily, we have some candy in our inventory which we offer him, and which he accepts. He doesn’t go away, though, which is what we hoped to achieve by giving it to him. Obviously there has to be another solution to the puzzle. Like riddles, puzzles always have a correct solution which is easily recognisable the moment we become aware of it: The phenomenon I have earlier described as a sudden moment of epiphany, borrowing the term from Espen Aarseth (Aarseth 1999).

The solution to this puzzle is to push away the garbage bin situated in front of the detective, dipping the candy in some green ooze that can be found underneath it in order to get “stinky candy”. When presented with stinky candy, the detective will gag and throw the candy away, accidentally hitting the man working nearby who will respond by attacking the detective with his broom and eventually chase him away. We now have access to the fuse box, where our next example of a puzzle takes place.

In the fuse box we find a damaged cable and a melted switch. We understand that there probably is a connection between this broken cable and some electricity problems bothering the man who works there, and decide to try to interfere, to see where that will lead us. But when we try, April refuses to touch the damaged cable, arguing that it might hurt her. Instead we look in our inventory for something that can function as protection against the current. We find a rubber glove that seems suitable for the job. But even while wearing the glove April refuses to touch the damaged cable. True, there is a hole in the glove which might be her reason for not trusting it to protect her sufficiently.

Consulting our inventory again for a better solution, we find a piece of band aid which can be used to patch the glove. April now agrees to use the patched glove on the broken cable, and we have solved another puzzle.

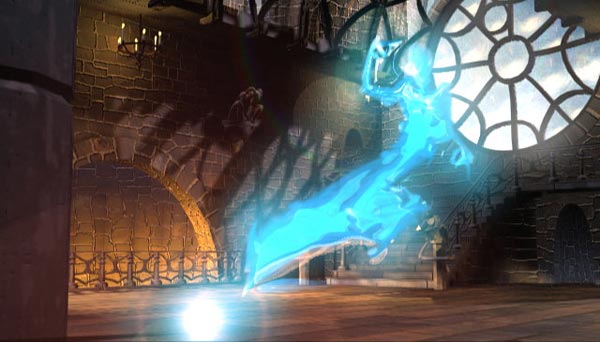

My third example occurs in chapter five, while we are situated in Arcadia, the parallel realm to Stark. As we remember, Arcadia is ruled by magic, whereas in Stark, science and logic rule. In this example, April confronts an evil alchemist who has captured the wind, as well as the souls of a great number of Arcadia’s inhabitants. April is here supposed to come up with a specific challenge in order to be able to defeat him. The puzzle is presented to us through the dialogue menu: “How about a real challenge?”, April provocatively mocks the alchemist. Then, after we have exhausted the options available in the menu – in which April presents the alchemist with a number of different types of challenges, all of which the alchemist perfectly masters – we are left to our own inventiveness. Meanwhile our opponent patiently waits for us to present him with a real challenge.

Again we consult our inventory, where we immediately recognise what must be the correct object and challenge: The calculator, which we mysteriously won at the cups game down at the market in Marcuria. “Mysteriously” because Marcuria is an Arcadian city, situated in the realm of magic where calculators don’t belong at all.

And of course it is the calculator. The alchemist may well be a master of magic, but as it turns out, he doesn’t know anything about arithmetic. Not even the simplest calculation is he capable of getting right. Having been defeated by our science representative three times in a row he summons the calculator from our hands and in possession of it seems to lose both his senses and his powers. Eventually he’s sucked into it and disappears.

(Figure 2.jpg) Copyright © Funcom 1998 - 2003

Puzzle analyses

Of the three puzzles I’ve just presented, this third one in which

April confronts the alchemist is definitely the most elegant. It is also

a better illustration than the two others of the features distinguishing

the riddle as a form or genre, in particular where complexity is concerned.

As I will try to show in the following analysis, this should hardly be

considered a coincidence.

The main difference between the puzzle involving the alchemist, and the two other puzzles, is that in the alchemist-puzzle, the world order reflected is different from the world order we are used to in real life. This puzzle requires specific knowledge of a fictional universe which functions according to certain laws that we must be aware of and identify in order to reach the puzzle’s solution. Without situating ourselves within the context of the fictional world of the game, and think according to the rules of the fiction, the puzzle cannot be solved. The game forces us to leave our familiar way of reasoning, and subject ourselves to the world of the game as if it were our reality. If Cohen is right, solving a riddle is experienced as an act of recognition – where what we recognise is an insight that was there all the time, that we knew even if we had temporarily forgotten it. In the same manner, by evoking an illusion of familiarity, a well constructed puzzle may function as a manifestation of our sense of knowing and belonging to the game world.

To a certain extent this is also accomplished in the puzzle in which we are supposed to mend the rubber glove using a band aid. However, a crucial difference between these two puzzles is that the referential frame for the rubber glove puzzle is based on knowledge acquired previous to the game, outside of its specific context: The knowledge called upon in order to solve this puzzle is accessible in our everyday life. Additionally, there is nowhere inside the game world where we may learn that rubber is resistant to current, and that this principle may be valid for band aid as well. The world order reflected in these rules is the same kind of world order that governs our everyday life, outside the game.

Thus the metaphorical tension which – according to Pagis – is present in well constructed riddles, preventing it from functioning like an ordinary problem which can be solved using logic alone, is lacking from this puzzle. Still the puzzle is not at all dysfunctional: It fulfils the requirement of being soluble, as all knowledge needed to solve it is readily available to any typical player. The somewhat unlikely operation of patching the glove with the band aid in order to make April agree to use it, prevents it from being entirely obvious as well. What is lacking from it is the tension between different world orders, which could contribute to the establishment of the game world as an alternative reality.

Considering our first example – which was how to make the detective disappear by offering him candy – we approach a worst case scenario, in which the puzzle ceases to even qualify as a puzzle. This one fulfils the minimal requirement of being non-obvious, in that our initial offers of candy to the detective fail to solve the situation. The problem of this puzzle is that it is hardly soluble: The world order it is based on, the rules of which the player is supposed to identify, is both illogical and unlikely. We have got no reason to believe that anyone would be fooled to accept – and then eat – stinky candy dipped in ooze, neither in our everyday world nor in the fictional context established by the game in which the puzzle occurs. If solving a puzzle is based on recognition, there has to be something to recognise. One of the characteristics of a good riddle or puzzle is that after we’ve solved it – or even been told its solution – this solution will appear obvious to us. If the solution still appears far-fetched it is simply not a very good puzzle.

A dysfunctional puzzle may of course serve a completely different purpose in the game, for instance being funny, absurd, educational, intertextual, ironic, or simply annoying. Still, as long as puzzle solving remains the main attraction of adventure games, identifying the features that are desirable and functional in a puzzle and distinguishing them from features that are not will represent a major task in conceptualising the genre. As I’ve attempted to show in this paper, I think that the model of the riddle may serve us as a useful analytical tool in this process.

References

Aarseth, Espen. 1999. “Aporia and Epiphany in Doom and

The Speaking Clock: The Temporality of Ergodic Art”, in

Marie-Laure Ryan (ed.) Cyberspace Textuality. Computer Technology

and Literary Theory. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University

Press. 31-42.

Cohen, Shlomith. 1996. “Connecting through Riddles, or The Riddle of Connecting”, in Galit Hasan-Rokem and David Shulman (ed.): Untying the Knot. On Riddles and Other Enigmatic Modes. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. 294-315.

Montfort, Nick. 2003a. “Toward a Theory of Interactive Fiction”. December 19. First published 8 January 2002. To appear in Emily Short (ed.) (2004): IF Theory. St. Charles, Illinois: The Interactive Fiction Library. Available online at http://nickm.com/if/toward.html [06.11.2005].

Montfort, Nick. 2003b. Twisty Little Passages. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press.

Pagis, Dan. 1996. “Toward a Theory of the Literary Riddle”,

in Galit Hasan-Rokem and David Shulman (ed.): Untying the Knot. On

Riddles and Other Enigmatic Modes. New York and Oxford: Oxford University

Press. 81-109.

The Longest Journey. Adventure Game. Funcom, 2000. The screenshots

used as illustrations in this paper are available at http://www.longestjourney.com/

[06.11.2005].

Tronstad, Ragnhild. 2004. Interpretation, Performance, Play, & Seduction: Textual Adventures in Tubmud. Doctoral thesis. Oslo: Unipub.